- Home

- Cheryl Bolen

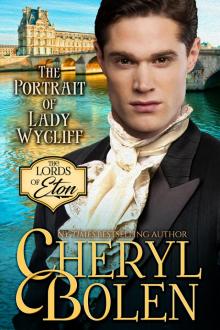

The Portrait of Lady Wycliff Page 2

The Portrait of Lady Wycliff Read online

Page 2

When all the women were gone, Harry turned to his cousin and spoke in a low voice. "Bloody bluestockings."

"A good thing they've no guillotine," Edward said.

Harry shook his head. "Violence, I should think, holds no appeal for these do-gooders."

A woman's voice responded. "That is absolutely correct, Lord Wycliff."

Peering at the angelic face of Mrs. Phillips, Harry could well believe violence was as alien to her as pock marks to her smooth, creamy skin. “I perceive you are a follower of Jeremy Bentham."

"I admire him greatly but am not a utilitarian purist," she answered.

"How gratifying," Harry murmured.

“Neither I nor Miss Featherstone,” the lovely widow said, turning to the plain young woman who stood beside her. Harry immediately felt sorry for the other female. How bloody unfair it was to have to be compared to the stunning Mrs. Phillips, for Miss Featherstone, though of the same age and similar stature, was possessed of unremarkable brown hair and an unremarkable face. She was, in fact, exceedingly plain—though not unpleasant. “Permit me to introduce my friend Miss Jane Featherstone to you, my lord.”

That lady curtsied.

Jane was an apt name for this plain Jane. Harry raised a brow. “You are related to the Mr. Featherstone who rather rules the House of Commons?”

A tiny smile seeped across Miss Featherstone’s face. “He is my father.”

“I do believe he’s acquainted with one my greatest friends. Sinjin, er, Lord Jack St. John.”

Both ladies’ faces brightened.

“We admire your friend very much,” Mrs. Phillips responded.

He smiled, then his gaze whisked from one to the other. “I am curious to know in what way do your views differ from Mr. Bentham's?"

The widow perused him through narrowed eyes. "Whereas Jeremy Bentham promulgates the greatest good for the greatest number of people — a belief that has much merit — I think that ignores the worth of the individual.”

Harry nodded. "Then you’re more of a Rousseau disciple?”

“If I were forced to choose between the two important thinkers, then, yes, I would prefer Rousseau.”

She looked skeptically at him and began to move from the room. "I suppose you would like to see your former residence?"

“Very much. In fact, I should like to make you an offer for the house."

She spun around to face him, her eyes flashing. "That you cannot do. I found out only this morning that I am not the owner."

"Then I beg that you direct me to the owner."

"That I cannot do."

Harry stopped in front of a massive painting of the Spanish Armada, a painting that had been commissioned by one of his ancestors in the early seventeenth century. "And why can't you, Mrs. Phillips?" Despite his efforts to conceal it, anger crept into his voice.

"Because I do not know who the owner is. My communication came through the owner's solicitor."

"Then if you will give me the solicitor's direction . . ."

"I will not." She stood in the doorway to the ivory dining room, framed in a golden radiance from the wall of uncovered windows.

Harry seethed. "May I ask why?"

She nodded, her manner haughty. "I dislike nobles."

Miss Featherstone gasped. “Really, Mrs. Phillips, you shouldn’t say that.”

“Oh, I don’t dislike you even if you are the granddaughter of an earl, nor does my dislike extend to Lord Jack St. John or his father, Lord Slade.”

“That I am happy to hear since St. John is easily a man for whom I would lay down my life.”

Harry had only barely resisted the urge to clasp his hands upon Mrs. Phillips’ shoulders and shake her. "Surely your study of equality has taught you that every man is an individual. Cannot I be given the opportunity to earn your respect before being dismissed as an idle noble?"

Edward pushed past Harry to confront Mrs. Phillips. "I'll have you know, my cousin here was left without two farthings to rub together, and by his own cunning has rebuilt his family fortune."

Harry watched the youthful beauty for a reaction, and when she turned her attention on him, he found himself reading her face as one reads Shakespeare, finding still another facet to admire.

"I hope you use your fortune," she said, "to improve the living of the cottagers who've toiled generations for Wycliffs." Presenting her back to him, Mrs. Phillips strolled toward the dining room.

“I say, Mrs. Phillips, that’s beastly unfair of you,” Edward said. “My cousin took care of all the Wycliff servants and cottagers before ever spending a tuppence on himself.”

The fair one looked contrite. “Forgive me, my lord. How rude you must think me.”

Harry stared her down until those pale blue eyes of hers blinked. “On the contrary, Mrs. Phillips, I think nothing of you. It’s my habit to reserve judgment until I’ve had the opportunity to get to know someone.”

Her lips pursed, and he detected a glint of humor. “Then as I’ve not had the opportunity to get to know you, I shall reserve my opinion as to whether you’ve just maligned me.”

He tossed his head back and laughed.

Which had the effect of cracking through his icy reception.

“I think you’ll find the dining room unchanged,” she said in a pleasant tone as she swept open its door.

Indeed, it was. Powerful emotions swamped him as he moved into the eerily silent room. These walls now so quiet had once echoed the lively conversations of prime ministers and heads of state, as much of England's business had been conducted at the very table Harry now surveyed. He could picture his father seated at the head of the gleaming mahogany table, surrounded by other members of the House of Lords and leaders of Commons. At the other end, his elegant mother would have sat, softly conversing.

His heart caught at the sight of the baroque family silver, the Wycliff crest etched on the footed teapot. His need to reclaim these possessions was as strong as his obsession to see them again.

A lump in his throat, he had to look away. Sunlight poured into the room from windows draped in faded gold silk. When he looked at the wall behind the head of the table, disappointment crashed over him. A Flemish tapestry hung where the Gainsborough portrait of his mother had been displayed for as long as he could remember. He wheeled around to Mrs. Phillips. "Where, may I ask, is the portrait of my mother which hung where the tapestry is now?"

She gave him a blank look. "I remember no portrait. What did it look like?"

"A typical Gainsborough. My mother was. . ." His voice gentled. "Very beautiful. She had golden hair and large, honey-coloured eyes. In the painting she wore a gown the colour of . . .” He pointed to a bowl of pale pink camellias. “Those.”

Mrs. Phillips shook her head. "I have seen no such painting in the eight years I've lived here."

Eight years? She would have been but a girl. He almost commented on it, but his need to see his mother’s portrait was stronger than his curiosity about the youthful widow. “You’re sure? It’s not in another room?”

Her features softened as she shook her head.

"Daresay it’s in the attic?" Edward offered.

Harry cast a hopeful glance at Mrs. Phillips. "With your permission, I should like to have a look in the attic."

"Certainly, my lord. You know the way, I presume."

"Of course." He and Edward went toward the stairs but turned back as Miss Featherstone took her leave. “I wish you luck, my lord.”

“Thank you, Miss Featherstone. It’s been a pleasure to make your acquaintance.”

* * *

Louisa Phillips stood at the bottom of the stairs and watched the back of the handsome nobleman whose censure she had drawn. She bit her lip. His reprimand had been well deserved, given the unfairness of her blanket dismissal of him, based on nothing more than the circumstances of his birth. Why, it was no better than throwing out the baby with the bath water! Erroneous preconceptions had been the very topic of one of her well-

received essays recently. Except the preconceptions cited in that tract dealt with lumping all cockneys in the batch with unsavory cutthroats because of their misfortune of birth.

Birth! She frowned as she retraced her steps to the drawing room. Lord Wycliff might not be an idle noble, but he was still an aristocrat. She bristled at the thought of them. They not only held all the land and wealth, they also hoarded legislative power, neglecting to write laws favorable to the individuals they repressed.

She had no admiration for those who sat back counting money earned by long-dead ancestors. Even though she was a woman who had been a dependent wife since the age of fifteen, she was capable of earning money by her own wits to put food on the table. She had managed to tuck away one hundred and fifty pounds from her essay writing. The money — as well as her authorship — had been hidden from Godwin. She had never willingly shared anything with her husband, much less her radical views which were so opposed to his Tory tastes. Never had he guessed the essayist Philip Lewis was his complacent young wife, Louisa Phillips.

Now she felt a tinge of remorse. Had she been saving the money from her writing so she could run away from Godwin? She had not allowed the intrusion of such thoughts while Godwin had been alive. And now it no longer mattered. She was free.

She felt wretchedly guilty over her lack of grief, but Godwin was not a nice man.

Her chest tightened. One hundred and fifty pounds would not go far if Godwin had not provided for her. She had always assumed this house would be hers. She was still reeling from the news that someone else owned the house she thought would come to her. Would all of Godwin's wealth also be taken from her?

What would she do? And how could she possibly make a home for her and Ellie if she were indeed penniless? Perhaps she should not have sent for her younger sister, Louisa thought, a sickening feeling in the pit of her stomach. It was too late now to withdraw the invitation. Ellie should arrive in London the next day.

She thought again of Godwin, and her hands curled into fists. Once more he had let her down. She strode angrily from the hallway, forcing her irritation onto Lord Wycliff. Even if he had soiled his noble hands making a fortune, Lord Wycliff was still born to the title, still confident he could swagger into his old home, make an exorbitant offer and once again possess the town house for which he held such an affinity.

She called for Williams. "You must put the chairs back as they were before the meeting," she told the butler.

"As you say, madam. A pity you must forever be telling me how to perform my duties. I should know that without having to be told."

Louisa looked kindly at him. "In time you will learn, my dear Mr. Williams. Remember, just a few months ago you were a gentleman's valet. You've learned much about being a butler, but it takes time."

With a mahogany chair in each hand, he strode across the room and replaced them at either side of the game table. "It's grateful I am that you've given me a chance."

"It's me," she reassured, "who is fortunate. You were a fine valet to Mr. Phillips, and you'll be an excellent replacement for Banbury, may God rest his soul." A sickening feeling surged through her. Surely Godwin had made provisions for Williams.

By the time she had instructed Williams in the drawing room, Louisa heard Lord Wycliff and his cousin coming down the stairs, and she hurried to greet them.

From the hollow expression in Lord Wycliff's dark eyes, she knew his search had yielded nothing but disappointment. "Any luck, my lord?"

"Unfortunately, no." He met her gaze, and she was taken aback by the grief she saw in his eyes.

"If I learn anything about the painting," she offered, "I will contact you."

He looked down at her. And she grew uncomfortable. The dark lord was exceedingly handsome. She had put away dreams of handsome lords when she abandoned dolls, already having been pledged to a well-to-do man who was older than her father. And in the eight years since, her eyes had never appreciatively swept across the figure of a good-looking man. Of course, she’d had no opportunity to do so — and of course, she loathed men.

With his sun-burnished face and well defined muscles, Lord Wycliff seemed out of place in a cut-away coat, freshly pressed cravat with silken vest, and pantaloons. She could imagine his muscled torso and generous shoulders rippling beneath the fine lawn of an unadorned shirt as he lunged with booted feet and swished his saber in the defense of damsels. She could even picture him hammering at a blacksmith’s anvil, sweat sheening his strong-boned face. Yet, despite the power and blatant masculinity he exuded, there was also tenderness.

"That would be most considerate of you," he said as he walked to the front door.

She wanted to do something that could balm the man's hurt. She almost offered the name of the solicitor, but that she refused to do.

After all, Lord Wycliff was an aristocrat.

* * *

The cousins settled in the carriage, then Edward turned to Harry. "I say, Mrs. Phillips could not have been much more than a babe when she wed that vile Godwin Phillips."

"I daresay you're correct." Harry spoke with no emotion, his thoughts low.

"Did you not think the widow's good looks rather extraordinary?" Edward asked.

Harry thought of the slim young woman who was such a paradox. Barely more than a girl, she bespoke the determination of a well-seasoned dowager. "I did. A pity she's a bluestocking."

"I thought you admired women who had a head on their shoulders."

“True, but there must be a compromise between stupid women and the bloody do-gooder bluestockings."

"Think I'd rather have a slow-witted wife," Edward said.

Harry’s dark eyes sparkled. “But I thought the idea of marriage was repugnant to you.”

“So it is. Never saw a girl more dazzling than a set of perfectly matched bays.”

A smile crept across Harry’s face. "Tomorrow, my dear cousin, we shall call on Mrs. Phillips for enlightenment."

Edward shot him a questioning glance.

Chapter 2

Louisa beamed at her younger sister, her eyes glistening. When she had last beheld her eight years ago, the ten-year-old Ellie had been all legs with uneven teeth too big for her dainty face. Now her legs were in perfect proportion to her woman's body. Her hair — once the same pale blond as Louisa's — was now the colour of summer hay. Still lightly freckled, Ellie's face had grown into her teeth—teeth that were now smooth edged, pleasantly even, and bright white. She had blossomed into a lovely young woman, Louisa thought with pride.

Though Louisa had successfully guided her sister, through her letters, in most matters of taste, she had failed to dissuade Ellie from wearing utterly feminine clothing. While her sister's frilly pink dress was perfectly acceptable, it was far too fussy for Louisa's taste.

"I cannot tell you how very good it is to see you," Louisa said, taking her sister's slim hand within her own. "Why, you're as tall as me!" She divested herself of her bonnet and moved into the foyer. "But very selfish I'd be to have you sit and chat with me when I know you must be weary from the journey."

"Not at all!" Ellie protested. "'Tis wonderfully good to be safe with you." She began to stroll carelessly throughout the first floor, unconsciously studying the opulent displays of wealth. "I declare, I had not a minute's peace during the whole of the trip. I kept remembering Miss Grimm's warnings about all the men having designs on my virtue."

Her older sister suppressed a chuckle. "You mustn't take Miss Grimm's advice too seriously, my pet." Taking her sister's hand again, Louisa led her to the drawing room and rang for tea.

"How blessed it will be to have tea in your lovely home." Ellie's gaze traveled the length of her sister. "London has been good to you. You're as lovely as when you left Kerseymeade."

Louisa shrugged and sat across from Ellie in a French chair upholstered in silk damask.

"I've missed you so," Ellie continued. "Why did you never return to Chewton Manor? Not even at yuletide?"

Louisa's

lips thinned, her eyes flashing. "You know what I told Papa when I left. I shall never forgive him."

"And you'll never again speak to him?"

Her eyes were cold. "Never."

"I must say, I, too, was glad to leave. I only hope London is not as wicked as Miss Grimm says, or I shall never set foot out your door."

"I assure you, you'll be quite safe with me." Louisa's voice softened. "Oh, Ellie, I have lived for the day you would turn eighteen and I could have you with me." Her gaze traveled to the window. "I vowed eight years ago I would get you away before he sold you, too."

"So, here I am," Ellie said, spreading her arms like an opera singer. "Shall I really get to meet Mr. Bentham?"

"Most assuredly," Louisa said.

"Papa would have apoplexy if he knew the contents of our letters, of our admiration for Mr. Bentham and the free thinkers."

Louisa's eyes twinkled, and she let out a little laugh. "Especially if he knew his eldest daughter was actually Philip Lewis."

"I must confess, Louisa, I did not at all like your last essay in the Edinburgh Review, though I have decidedly agreed with all your previous writing."

"The one against marriage?"

Ellie nodded as Louisa poured tea into two dainty porcelain cups and handed one to Ellie. "Just as one apple does not spoil the whole bunch, I think your bad marriage should not poison you completely against matrimony."

"It's not just my own unsatisfactory marriage," Louisa defended, "but the system. Classes marrying within classes. Women forced into matrimony . . ."

"But you advocated free love!" Ellie shrieked. "Have you actually taken lovers?"

That hard look came back on Louisa's face when she shook her head. "I have yet to meet the man upon whom I could freely bestow so intimate an offering."

Folding her arms, Ellie shot her sister a reproachful look. "I believe you dislike men."

Louisa bit her lip and did not respond for a moment. "I will own my only experiences with men — with Papa and with Godwin — have not shown their sex in a favorable manner. I do not believe there is such a thing as an honorable man."

A dreamy look came over Ellie's face. "I believe I shall find an honorable man."

With His Lady's Assistance (The Regent Mysteries Book 1)

With His Lady's Assistance (The Regent Mysteries Book 1) Once Upon a Time in Bath

Once Upon a Time in Bath One Room at the Inn (The Lords of Eton Book 4)

One Room at the Inn (The Lords of Eton Book 4) His Lady Deceived

His Lady Deceived Last Duke Standing

Last Duke Standing Counterfeit Countess: Brazen Brides, Book 1

Counterfeit Countess: Brazen Brides, Book 1 A Duke Deceived (The Deceived Series Book 1)

A Duke Deceived (The Deceived Series Book 1) An Egyptian Affair (The Regent Mysteries Book 4)

An Egyptian Affair (The Regent Mysteries Book 4) Winter Wishes: A Regency Christmas Anthology

Winter Wishes: A Regency Christmas Anthology A Most Discreet Inquiry (The Regent Mysteries Book 2)

A Most Discreet Inquiry (The Regent Mysteries Book 2) The Portrait of Lady Wycliff

The Portrait of Lady Wycliff A Lady by Chance (Historical Regency Romance)

A Lady by Chance (Historical Regency Romance) His Lordship's Vow (Regency Romance Short Novel)

His Lordship's Vow (Regency Romance Short Novel) Lady Sophia's Rescue (Traditional Regency Romance)

Lady Sophia's Rescue (Traditional Regency Romance) A Birmingham Family Christmas

A Birmingham Family Christmas Oh What A (Wedding) Night (Brazen Brides #3)

Oh What A (Wedding) Night (Brazen Brides #3) A Christmas In Bath

A Christmas In Bath THE BRIDE WORE BLUE

THE BRIDE WORE BLUE Miss Hastings' Excellent London Adventure (Brazen Brides Book 4)

Miss Hastings' Excellent London Adventure (Brazen Brides Book 4) Marriage of Inconvenience

Marriage of Inconvenience Ex-Spinster by Christmas: House of Haverstock, Book 4

Ex-Spinster by Christmas: House of Haverstock, Book 4 With His Ring (Brides of Bath Book 2)

With His Ring (Brides of Bath Book 2) The Theft Before Christmas (The Regent Mysteries)

The Theft Before Christmas (The Regent Mysteries) The Theft Before Christmas

The Theft Before Christmas To Take This Lord (The Brides of Bath Book 4)

To Take This Lord (The Brides of Bath Book 4) Countess by Coincidence

Countess by Coincidence Captivated by His Kiss: A Limited Edition Boxed Set of Seven Regency Romances

Captivated by His Kiss: A Limited Edition Boxed Set of Seven Regency Romances A Birmingham Family Christmas (Brazen Brides Book 5)

A Birmingham Family Christmas (Brazen Brides Book 5) My Lord Wicked (Historical Regency Romance)

My Lord Wicked (Historical Regency Romance) A Duke Deceived

A Duke Deceived The Earl, the Vow, and the Plain Jane

The Earl, the Vow, and the Plain Jane The Bride's Secret

The Bride's Secret The Earl's Bargain (Historical Regency Romance)

The Earl's Bargain (Historical Regency Romance) Rebels, Rakes & Rogues

Rebels, Rakes & Rogues One Golden Ring

One Golden Ring